In 1954, Time magazine published a short column listing three civil rights breakthroughs (and one “no-gain”) that included Knoxville integrating its airport restaurants and Birmingham allowing Black and white athletes to compete against each other in baseball and football. It’s a short list, presented straightforwardly, except for one phrase in the first sentence: “to breach the Magnolia Curtain of racial discrimination.” Those words—a bit of poetry in the newsreel—implied a truth both obvious and largely unspoken: The South had used its prejudices and its claims to heritage, among other bricks and mortar, to cordon itself off from the rest of the nation. The phrase took hold and proved useful during the Civil Rights era, and in 1964, when a self-proclaimed “New York liberal” writer named Richard Boeth moved to the small town of Rosedale, Mississippi, he gleefully annihilated the region’s calcified hypocrisies for The Atlantic. He called the piece “Behind the Magnolia Curtain.”

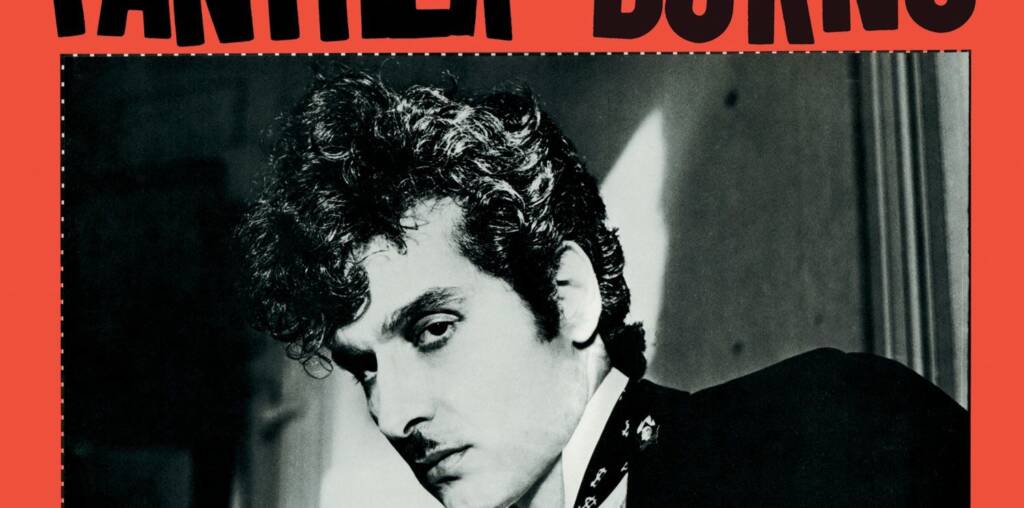

In 1981, Memphis musician Tav Falco adopted that same phrase for the title of his debut album with the Panther Burns, one of the weirdest, wildest support groups in rock history. His usage seems less pointed than Boeth’s, on account of him being an actual Southerner; Falco might have been born in Pennsylvania, but he grew up near Gurdon, Arkansas, moved east to Memphis as a young man, and has been closely associated with that city ever since (despite spending the past 30 years living in Europe). He’s always been on the southern side of the Magnolia Curtain, so he can see what it conceals from those who erected it in the first place: a vibrant culture that extends to food, clothes, literature, and especially music, too often disregarded or overwritten by modern Southerners.

No score yet, be the first to add.

Or, as he told a combative TV host during a famously tense Panther Burns performance in 1979: “It’s all invisible to us.” And by “us” he means not himself or his band, but Memphis in general, the South in general. Everybody down here. “We can’t see what’s around us. There are blues people here who don’t have exposure, rockabilly artists who don’t have any exposure. They don’t really exist here. They’re part of our environment, we see them every day, yet they’re invisible to us. We take them for granted. It takes a group like us to create contrast, to create focus.”

Panther Burns wanted to jolt their listeners into seeing those invisible people—those old blues and rockabilly artists whose innovations defined the city’s culture even after they were forgotten. The way they did that was by playing old songs very loud and very bad. At any given moment each musician in the band might be playing at a different tempo or in a different key altogether, or hell, they might be playing a completely different song. On a good night they could make the Shaggs sound like Booker T. & the M.G.’s. Panther Burns weaponized their amateurism, but never condescended to the source material: Falco wanted to make that old music as culturally disruptive in the late 1970s as it had been in the late 1950s. The best way to do that, he reckoned, was volume and chaos.

That strategy was evident enough in his first public appearance, when the man born Gustavus Nelson gave birth to a legend named Tav Falco. The scene takes place on the afternoon of October 1, 1978, at the Orpheum Theatre, then a rundown building with broken seats and peeling paint, lacking heat and constantly in danger of demolition. It was, in other words, a perfect symbol of the city’s withering music industry. Elvis had died, and while his death eventually inspired a morbid, kitschy cottage industry, he was still dead. Stax had closed, shuttered by some shady dealings by Atlantic in New York and Union Planters Bank in Memphis. Chips Moman had closed American Recordings, where the Box Tops, Bobby Womack, and Dusty Springfield had recorded huge hits. And Al Green, the city’s last major superstar—at least for a while—had ditched Hi Records and bought a church. In a downtown emptied by white flight and recession, the Orpheum was used primarily for DIY events, which is why Jim Dickinson chose the spot for a series of shows celebrating local music. The very last one he advertised as the final performance by his band Mud Boy & the Neutrons, although he knew full well the band wasn’t going away.

Midway through Mud Boy’s mock send-off, Falco wandered onstage looking like a punk Charlie Chaplin: pencil-thin mustache, tattered tuxedo, and frayed, fingerless gloves. Strumming an out-of-tune guitar, he delivered a crude and shrill yet impassioned cover of Lead Belly’s “Bourgeois Blues.” He caterwauled the chorus—“It’s a bourgeois town!”—as an accusation to a city that was ignoring its greatest resources, namely its legacy of blues, country, rockabilly, gospel, and plum weird shit. He then set his Silvertone down on a chair, produced a chainsaw seemingly out of nowhere, and set about loudly splintering the still-plugged-in guitar. It was so loud, so violent, so intense that Falco reportedly ended his short set by fainting.

Nobody could have known at the time, but that performance was a prophecy of the city’s future, where artists would become the primary stewards of Memphis music history, rampaging through old blues, rock, soul, and gospel. The audience was small that afternoon—roughly 50 people in the 2,300-seat venue—but Alex Chilton was there, and he liked what he heard. He saw great promise in the collision of punk and performance art, blues and noise, reverence and irreverence: local music history as a vehicle for local commentary and local confrontation. Chilton had been up in New York City, off on the fringes of the punk scene and catching shows by James Chance & the Contortions and Teenage Jesus & the Jerks, and he saw the potential in Falco for a uniquely Memphis take on no wave, anchored in the musical traditions that made the city famous. He suggested to Falco that they start a band—not as equals, not like him and Chris Bell in Big Star, but with Chilton as sideman and Falco as bandleader. They rounded out the group with some local professionals (like bassist Ron Miller, a member of the Memphis Symphony) and some friends unburdened by musical talent (like drummer Ross Johnson, who by his own admission was no drummer). “I’m really not even a musician,” Falco explained to Memphis’ Commercial Appeal. “I just make music and play upon the guitar.”

That band name—Panther Burns, sometimes the Unapproachable Panther Burns—comes from a town deep in the Mississippi delta, about an hour south of Memphis. The word “town” might be an exaggeration: It’s more like a strip of highway with aspirations of incorporation. Falco knew about its lore, how a panther once stalked the community for months. The animal was so massive and powerful that its mighty tail swept loose the earth behind it, erasing its footprints and making it impossible to track. Finally the local sharecroppers trapped the beast in a cane break, which they set on fire rather than kill it by hand. For their cowardice they suffered a long night listening to its dying shrieks. Falco wanted the band to make music that sounded like the cries of a conflagrating cat; he wanted to keep folks up at night.

Just four months after that Orpheum performance, Falco and his new band played their first show at 96 S. Front Street, an old cotton exchange building that had once housed a segregated “soft drink” establishment and an off-the-books whiskey service in the 1920s but had sat empty for decades. Besides the Orpheum, there weren’t many places in Memphis where punk and no wave or new wave bands could play, so they had to create venues for themselves in the vacant historic buildings overlooking the Mississippi River. Falco didn’t brandish a chainsaw, but the band exerted a similar effect on the songs they covered. They played with fury and abandon. They made the invisible briefly visible. Some folks left plugging their ears, but enough stayed to crowd the stage. Realizing he was boxed in, Chilton stepped to the side, unzipped, and relieved himself mid-song.

Onstage, Falco appeared like a man from another time, cajoling his audience and even calling them “lackeys of the running dog imperialists.” Away from the stage, however, their mission to illuminate the dark corners of Memphis history through volume proved much more daunting. They recorded covers of “Train Kept a Rollin’” by Johnny Burnette and “Dateless Night” by Allen Page, two local rockabilly pioneers by then largely forgotten. That single caught the ear of Rough Trade founder Geoff Travis. He encouraged Panther Burns to record and submit a full album of material, so they booked time at Sam Phillips Recording Services. Jim Dickinson stepped in to produce and play a little piano, but Travis deemed the results too polished, too polite, too bourgeois. Where was the noise? The subversion? The disruption? (Those recordings were released in 1992 as The Unreleased Sessions.)

Falco and Panther Burns regrouped and booked two three-hour sessions at Ardent Records in Midtown, once hectic with overflow from Stax but now booking sessions with national acts like ZZ Top. They took a first-take, best-take approach to recording, not necessarily racing through the songs but certainly not taking their time to get everything just right. Comprised primarily of covers of Memphis non-hits, Behind the Magnolia Curtain is a bizarre record, its confrontational lack of chops intensifying its cockeyed charisma and ribaldry. Sex—once so repressed by polite society that it bubbled up in disreputable music—motivates many songs, especially on the first side. Their cover of Page’s “She’s the One That’s Got It” plays coy with its subject matter, especially when the band begs him to elaborate. “Got what?” they bark at him. “Oh, you know!” comes the reply. Somehow it sounds racier than if he were more explicit.

That weird discretion makes his takes on “Come On Little Mama” and “Hey High School Baby” less troublesome than, say, the Stray Cats’ “She’s Sexy +17,” which far too eagerly broadcasts its lecherous designs. Those historical re-enactors from Massapequa were taking rockabilly back into the Top 10, but lesser-known bands like the Blasters and, in particular, the Cramps were cratedigging for left-of-center inspiration and putting their own indelible stamps on old blues and rockabilly numbers. Behind the Magnolia Curtain, though, sounds like an album that could only have been made in Memphis by artists steeped in local lore, by folks who drove by the boarded-up Stax building every day, who maybe bumped into Furry Lewis sweeping up on Beale Street, who knew where all the bodies were buried. It’s full of big ideas, but never sounds brainy or abstract. It’s always specific, always purposeful, always lurid. Behind the Magnolia Curtain kicks you in the head and the gut, and then it kicks you in the ass.

There’s an intimacy with the source material, but also a sense of immense possibility. Falco invited members of the Tate County Mississippi Drum Corps up to Memphis to play on the record, and you can hear their booming bass drums and slithering snares on their version of R.L. Burnside’s “Snake Drive” and Ary Barrosso’s “Brazil.” The latter is one of the most covered songs of the 20th century, but that bouncing chorus of drums, along with Falco’s marblemouthed croon, utterly transforms the melody. This melding of punk and fife-and-drum blues has inspired locals for years, including one-time Panther Burns guitarist Lorette Velvette (“Come On Over”) and the Oblivians (“I May Be Gone”).

Rough Trade picked up Behind the Magnolia Curtain, and soon the Panther Burns were on the road more than they were in Memphis, with a lineup that changed almost every night. A few members played only one show, others even less. The official list of players past and present includes old-timers like Burnside, the Memphis Horns, Teenie Hodges of the Hi Rhythm Section, and the Bar-Kays’ Ben Cauley, along with younger artists like Jim Duckworth (of the Gun Club), Jim Sclavunos (Teenage Jesus & the Jerks and later the Bad Seeds), Alex Greene (Reigning Sound), Roland Robinson (who wrote Rod Stewart’s hit “Infatuation”), and many others. Chilton left the band not long after recording Magnolia Curtain, but his short tenure invigorated him: You can hear him tinkering with these ideas throughout his career, especially on his 1979 solo debut, Like Flies on Sherbert. Finding intention in inscrutability, he forged a way forward.

For Falco, it was impossible to sustain that chaos of possibilities, and not just because the musicians in Panther Burns couldn’t help but hone their chops. Folks get used to loud and bad, they adjust to the din, so the visible becomes invisible once again. His subsequent albums, including 1987’s excellent, Chilton-produced The World We Knew, burrow deeper into his own persona, which is eccentric and mysterious in a specifically Southern way. He left Memphis for Europe in the early 1990s, perhaps with the idea that the best way to understand your home is to leave it, yet he remains closely associated with that city as a soapbox historian, always beating the drum for the forgotten and the never-known. With Behind the Magnolia Curtain, he showed generations of locals how they might rediscover and redefine Memphis music, how they might draw back the curtain once more.