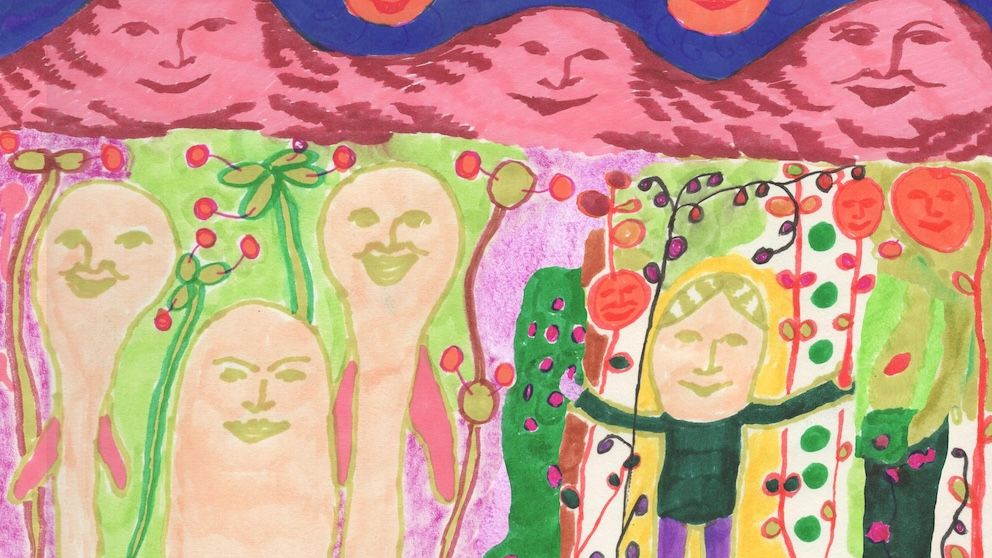

When I was 14, my friend and I visited a store called the Happy Herb Shop. We wanted to buy mugwort, because we had become obsessed with the idea of lucid dreaming and were in dogged pursuit of any substance that could assist our attempts to move through our dreams with conscious intent. I can’t say that the mugwort worked; the tea was disgusting and we couldn’t successfully smoke it, because we didn’t know about those magical little things called “rolling papers.” But I still remember what I thought lucid dreaming would feel like: A journey into some kind of purple-blushed twilight zone where familiar things felt unreal but welcoming, and the atmosphere didn’t correspond with any sense of earthly physics. I thought it would feel like Peanut!

Peanut is the sixth-ish album by New York-based musician and engineer Otto Benson, and the first with vocals. He shed a lot of skin before arriving at this album’s dusky, dusty sound, which is defined by gentle nylon-stringed guitar and shivery Rhodes piano and lands somewhere at the intersection of Frankie Cosmos, Hayden Pedigo, and Let It Die-era Feist. A scan of his meticulously maintained website reveals a trove of hyperactive vaporwave under the name Memo Boy; ambient music as Ronnie P; puckish hyperpop under the name OTTO; a tingly beat tape with Mietze Conte; and at least a handful more experiments with different forms of contemporary electronic pop. The first time I saw Benson live, supporting Jessica Pratt in a former bingo hall in Jersey City, he performed alongside a robotic MIDI glockenspiel rig he had built himself.

No score yet, be the first to add.

All of this is to say that form is clearly important to Benson; although Peanut is his first album with lyrics, it isn’t so much his “first real album” as it is one shapeshift among many. The first song, “Mr. Peanut,” is wordless and speaks volumes: It opens with a clattering kick, one of the album’s only drum sounds, as if Benson is shaking off all the hyperactive noise of past projects, only to give way to a searching, somnambulant guitar line that floats through the rest of the track. It’s the next song, “Red and Neon,” that seems to clue you in to what’s happening: “I’ve been here for hours/Or maybe days/My mind runs in circles/And the disco fades away.”

Of course, that’s an extraordinary literal reading, perhaps one not warranted by such circuitous, exploratory music. Songs like “Red and Neon” and “Raisin” are relatively simple on a structural level—few chords, few parts—but they maintain a strong sense of the psychedelic. Two thirds of the way through the former, a loose solo begins to float atop the track, like a moth fluttering around the corner of a projector screen: small enough to theoretically ignore, but present enough to draw your attention. On “Raisin,” Benson sings off-kilter images in a quotidian way: “Chasing a beetle from a photograph/Couldn’t catch it but I’m off my ass/Thought I saw another but it was just a raisin.” He repeats the title word over and over, drawing it out like an old crooner would sing the name of a lost lover, making an errant piece of dried fruit sound like the most important speck in the universe.

Benson’s voice imbues this music with gravitas: He sings in a high, quiet warble that gives his lyrics a pervasive weariness, even though they’re rarely prescriptive when it comes to their meaning. The most clear-cut song on Peanut is “Tumor,” which, if hardly a transparent breakup song, at least captures the feeling of not wanting to say goodbye to something: “There’s a tumor/It’s growing bigger,” he sings softly, “It’s looking at you/And says with a whisper/Drive slower.” Toward the end, entropy begins to slip into the frame: a high-pitched ringing, echoing feedback, watery static. It is a gut-wrenching song, perhaps because of its obliqueness: It ends abruptly and uncomfortably, cruelly denying any real sense of resolution.

The vocals on Peanut serve a simple purpose: Even on a song like “Car Wash,” which ends with the lines “I am clean/Like the head of butterbean,” they affirm that this music is emphatically, avowedly human. Although that’s a simple and maybe obvious idea, Benson has suggested in interviews that he’d like his music to feel detached from automated and algorithmic processes. He has retired the glockenspiel because he wants to “lean into a more human expression and connection with people,” and says he “take[s] a lot of issue with” the fact that many artists feel forced to feed into the whims of social media algorithms. (His Memo Boy song “Insomniac” went viral on TikTok.)

Hence Peanut, which sounds like an attempt to translate an internal world into something that others can hear too. A lot of the vocals on the album aren’t even words, just na-na-nas and da-da-das; the clearest images, like fingernails that “twist all around you and wrap around your arms,” feel like they’re wrenched from deep within Benson’s psyche, warped and prosaic at the same time. Perhaps not lucid dreams, but elucidating ones.