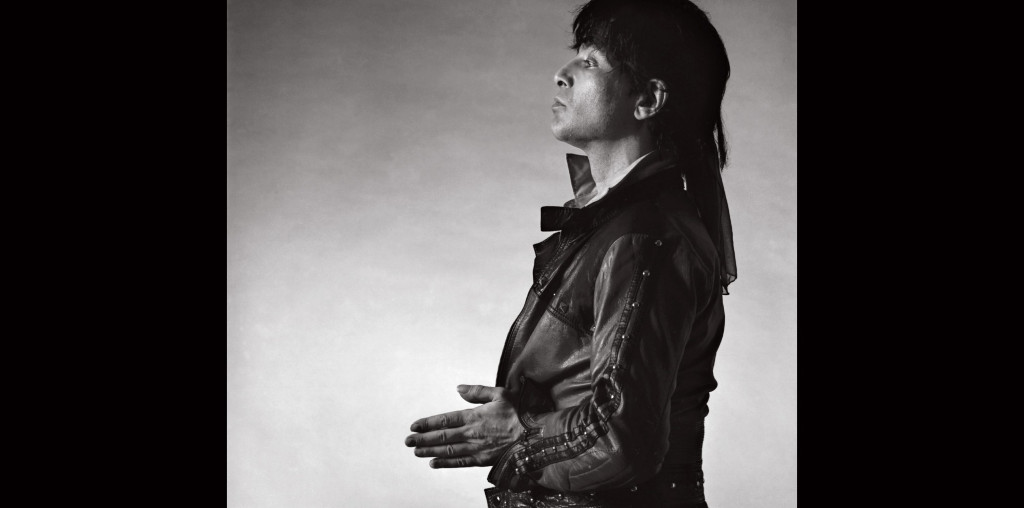

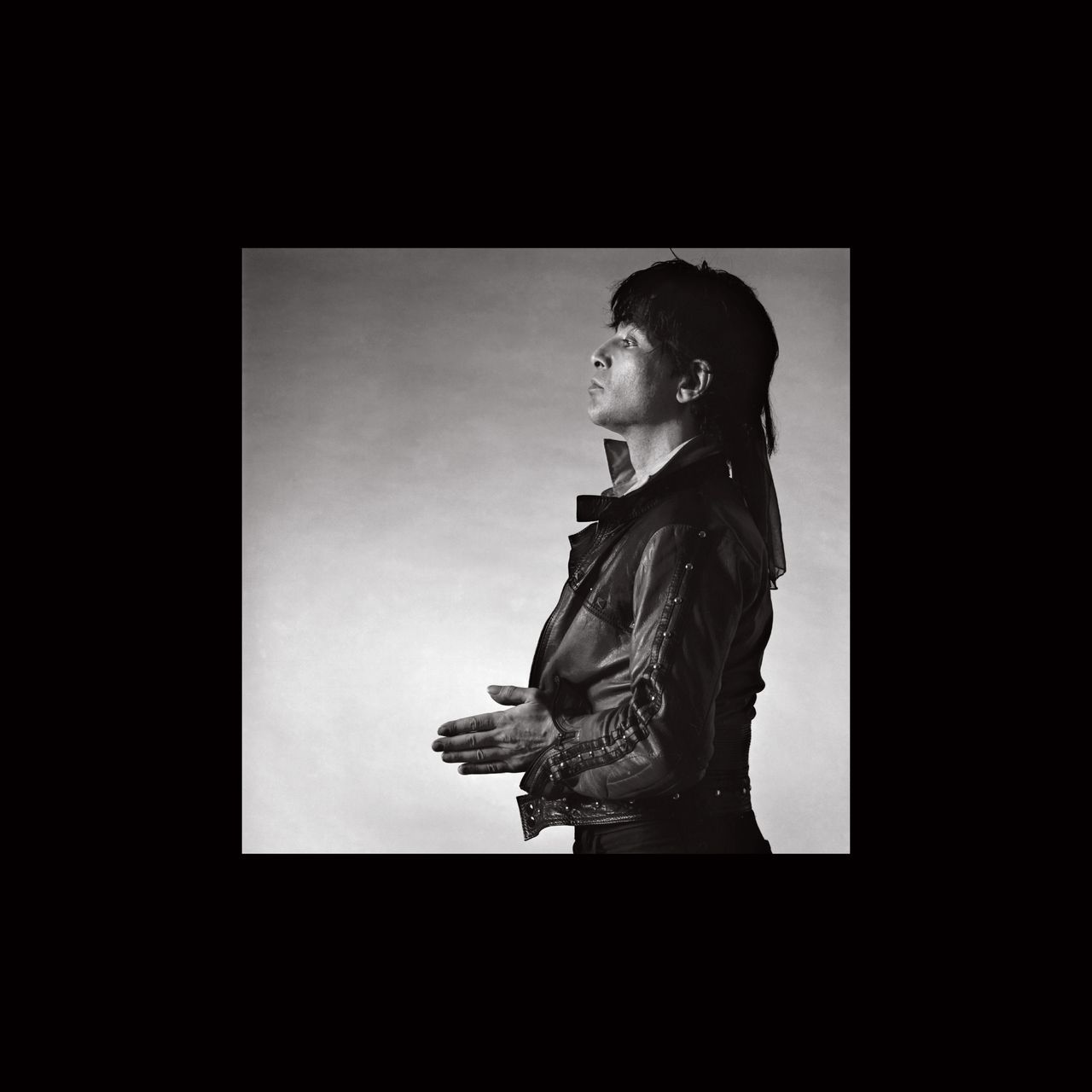

By the end of 1980, after 10 years waiting for the world to catch up with them, things were looking bleak for Suicide. The pioneering New York electronic project of keyboardist Martin Rev and vocalist Alan Vega had released a sinister self-titled debut in 1977; the album was met by hostility from crowds and mocked as “puerile” by Rolling Stone. Playing on tour with Elvis Costello, the Clash, and the Cars, they’d been pelted with shoes, coins, and even knives. ZE Records had backed May 1980’s glitzier follow-up, Suicide: Alan Vega and Martin Rev, putting the duo in the expensive Power Station studios with the Cars’ Ric Ocasek on production. But the label had hoped for a dance-pop record, telling Ocasek to think of Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” for reference, and Vega felt it underperformed. “I was on the way out,” he later told NME.

In fact, Vega was about to enter a new chapter. “I had always wanted to do a rockabilly record,” he claimed in the 2004 biography Suicide: No Compromise. He’d do so with his November 1980 solo debut Alan Vega, assisted by guitarist Phil Hawk, before recruiting a full band for 1981’s Collision Drive. Compared to Suicide’s groundbreaking early work, these more conventional-seeming albums are less often revisited. Sacred Bones’ new joint reissue prompts their reappraisal as complex, fascinating records that offer a better understanding of Vega himself.

No score yet, be the first to add.

Alan Vega continues Suicide’s interest in minimalist instrumentation and linear structures, but trades Rev’s avant-garde electronics for Hawk’s more digestible, Eddie Cochran-esque guitar. The easy charm of tracks like “Jukebox Babe” reveals that, despite his antagonistic persona, Vega had some commercial aspirations—he’d written the song to be a hit, breaking the French Top 10. The album’s devotion to rockabilly, name-checking its progenitor Johnnie Ray on “Jukebox Babe,” also lays bare what an important ingredient the style was to Suicide. Publicly believed for most of his life to have been born in 1948, Vega was actually 10 years older, coming of age during the ascent of Elvis Presley and Gene Vincent. Listening to Alan Vega, these rockers’ influence on his signature howls and croons becomes obvious.

But Alan Vega is deceptively weird—designed, Vega would later tell NME, to “extend the boundaries of rockabilly.” The mixed acoustic and electronic percussion, like the tinny drum machines and handclaps on “Speedway,” produces an odd texture and sense of space. Lyrically, it’s a dreamlike collage of fantasy, horror, and Americana: “Ice Drummer” drifts between a Chevy-driving werewolf and a “little drummer boy frozen by fear,” heralded by a military drumroll. There is also some of Suicide’s defining tension, from the eery “Kung Foo Cowboy” to the “burned-out maniacs holding dynamite” on “Fireball.”

The deluxe Alan Vega LP seeks to illuminate Vega’s process with demos of all songs except “Jukebox Babe.” Most are disappointingly close to the final versions, except for a striking draft of closing ballad “Lonely”: The Alan Vega version features the sinewy croon honed on Suicide tracks like “Dream Baby Dream,” but on the meandering, almost double-length demo, he sounds feeble—revealing how deliberately the man born Boruch Alan Bermowitz transformed to become rock star Alan Vega. The deluxe edition sleeve features pages from a notebook he’d used for song ideas and sketches of drum machine settings; one page outlines proposed tracks for “Ice Drummer,” envisaging male and female voices, saxophone blasts, and breaking bottles. Far more complex than the final recording, it suggests Vega had plans for less minimalist solo work—the sort he’d pursue on Collision Drive.

Trading Alan Vega’s skeletal sound for the dynamism of a full band, Collision Drive is less experimental but stronger as an actual rockabilly record. Comparing peppy opener “Magdalena 82” or ballad “I Believe” to their Alan Vega counterparts “Jukebox Babe” and “Lonely” demonstrates how, in this case, Vega’s embrace of genre convention produced better songs. He further aligns Suicide and rockabilly with two covers, giving Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-a-Lula” some newfound animalism and rendering Suicide’s own “Ghost Rider” with the kind of period rock’n’roll instrumentation that Vincent might have used. Collision Drive doesn’t so much complete Vega’s reinvention as a rockabilly artist so much as reveal that he’d always been one.

Self-reinvention gets sidelined for the duration of Collision Drive’s horrifying, nearly 13-minute closer, “Viet Vet,” a companion of sorts to Suicide’s portrait of a factory worker in “Frankie Teardrop.” Over a slow groove, distant moans, and wailing guitar, Vega depicts an injured veteran who’s driven to petty theft. “You owe me a debt!” he screams at pursuing police. The song lacks the airless electronics that gave “Frankie Teardrop” its tension, but its American rock sheen lends irony to Vega’s critique of post-Vietnam War patriotism. While “Viet Vet” sounds out of place on Collision Drive, it heralds Vega’s eventual return to more experimental, provocative work with Suicide later in the decade.

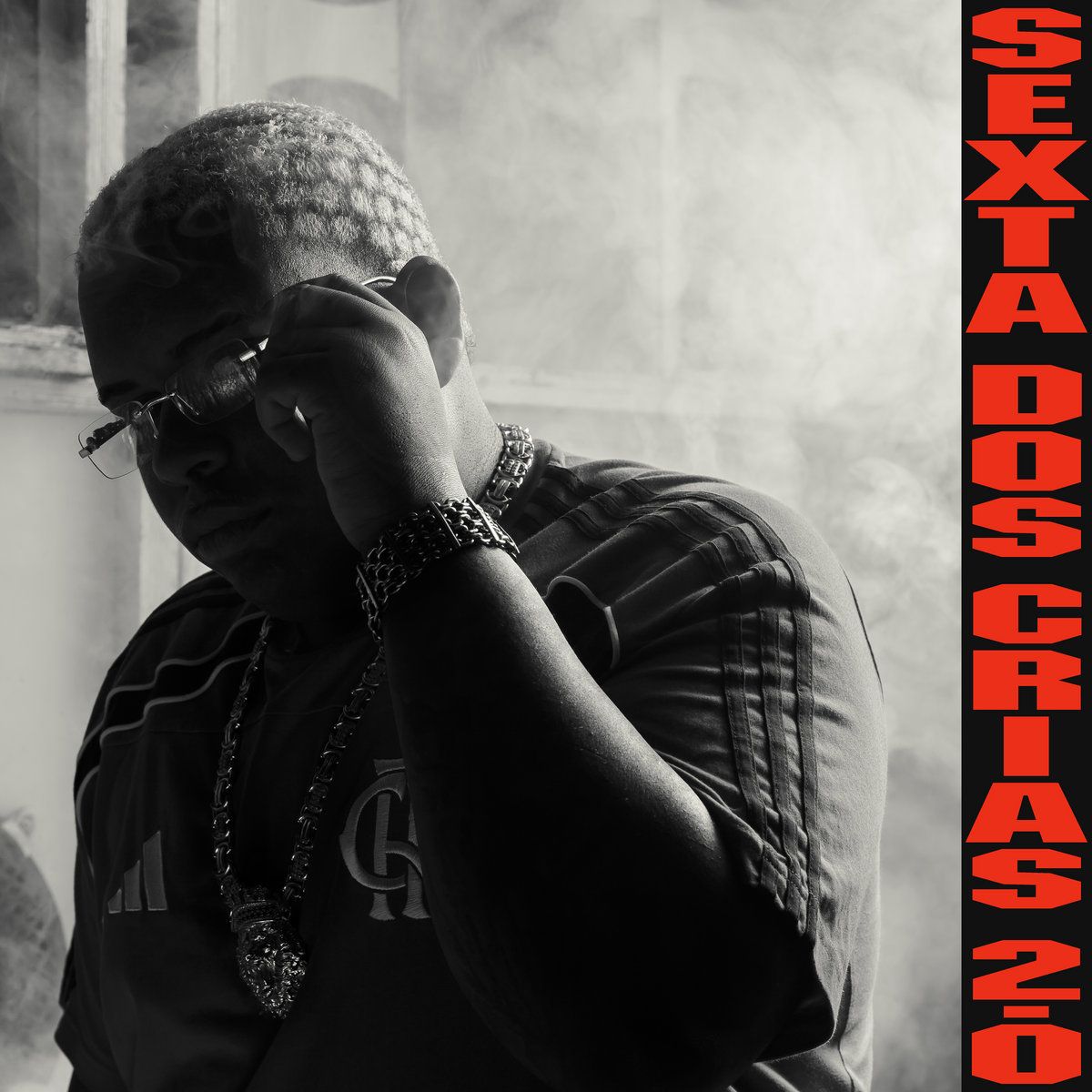

The Alan Vega and Collision Drive reissues are best enjoyed by Vega fans looking for new insights, but these largely lie in the music itself: While the LP packages are well-presented, including the notes in Alan Vega and alternative cover photos for Collision Drive, the demo recordings are too close to the final versions to add much interest. Newcomers may simply enjoy Vega’s effort to take vintage rockabilly to subversive new places: Even in this more commercial chapter, as he sings on “Jukebox Babe,” Vega was “playing a strange game.”