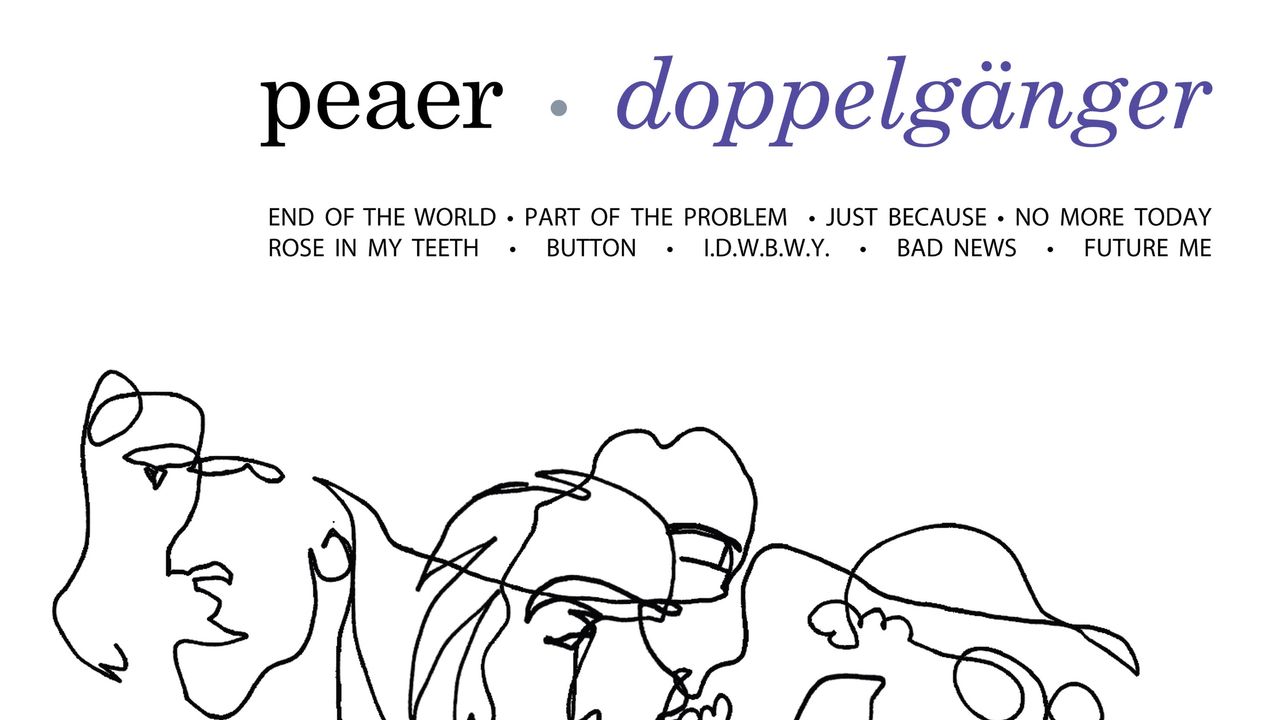

A crucial question comprises the syncopated chorus of “Bad News,” the penultimate track on Doppelgänger. “Who do you wish you were when you’re alone?” Peaer’s lead singer Peter Katz asks in falsetto. Self-directed inquiries make up the bulk of Döppelganger’s lyrical content, and the album’s quiet unrest makes it clear that he has been stewing on this particular question for longer than he ever wanted to. When lockdown prevented the Brooklyn trio’s tour in support of 2019’s A Healthy Earth, Katz stopped making music altogether for a full year. He’d formed his band and signed to Tiny Engines while studying at SUNY Purchase (a retrospective incubator for Bandcamp-era indie rock success stories of the 2010s), and music had defined almost the entirety of his adult life. But what was once a life force had become a breeding ground for resentment toward the industry and its gatekeepers, as well as toward the person he was onstage and on his records—a person he no longer recognized.

Some of Doppelgänger’s best songs synthesize years of working and reworking, stagnancy and revival, in just a few minutes. “No More Today” was written in 2018, and it hints at the burnout that eventually led to Katz’s hiatus. Its ghostly guitar melodies float as its basslines thud along, growing both more menacing and dejected as Katz’s depression becomes impossible to outrun. Katz wrote “Part of the Problem” during the 2016 election. Its lyrics are vague enough (and our circumstances unfortunately similar enough) that it doesn’t feel stuck in the past. The message—frustration with a crisis that can’t be solved with one single action, a general wariness of anyone who claims to have all the answers—is timeless. So is the simple and slow chord progression underlying it all, making for a folk song that avoids the predictable tropes of protest music and doesn’t rely on cynicism as a dead end.

No score yet, be the first to add.

The creeping riff that serves as a skeleton for “I.D.W.B.W.Y.” dates all the way back to 2015, but the lyrics weren’t written until five years later. They’re few and purposely ambiguous. A solemn stack of harmonies repeats “I don’t wanna go back there” and “I don’t wanna be without you” for the first and second choruses respectively, like mantras. “I.D.W.B.W.Y.” could be interpreted as a pure love song just as easily as it could be a lament about a codependent relationship or a breakup song stuck in the denial stage of grief. Most of Doppelgänger expands Peaer’s signature slowcore into something more melodic, but “I.D.W.B.W.Y.” hearkens back to a more bare-bones era of the band’s sound. It’s lived-in without being worn out.

Throughout the album, Katz questions how much identity stock to put into being an artist, whether continuing to pursue a music career is worth the financial precarity and psychological strain, and if what he’s building is “just a shrine to [his] ego.” He’s steeped in the less glamorous half of a double life on “Button,” marching up and down the scale and interrogating his decision to take on a 9-5 office job: “Plan every step, once it’s done, nothing’s left/Did you make it?” The barely audible scratching of strings twitches in the periphery, adding a subtle daydreaming quality to Peaer’s otherwise grounded song construction. Katz’s cryptic mumblings referencing Biblical imagery and Greek myths make “Rose in My Teeth” feel out of place. Still, it’s an instrumentally striking track, built around a twisting, American Football-reminiscent riff.

Closer “Future Me” is a straightforward address to a version of Katz that he hasn’t yet become. Recorded on an iPhone, its production strays slightly from the relative cleanness of the rest of the album, letting you hear each time Katz’s breath catches or wavers. It sounds like a voice memo pulled from the drafts and forced into the public without necessarily being ready—perhaps like Katz himself. The album closes mid-word, while Katz is repeating the refrain of “Have you given up on everything?” It’s a fitting end to a record largely made up of unanswered questions: leaving us not only without an answer but also with the question itself cut short. As much as Doppelgänger is a testament to slowing down and letting good things take time, there’s a stark humanity in its awkward in-between stages. It’s a strange and disquieting document of an artist falling out of love with music and a band finding its footing again.