Jill Scott’s music feels like Black memory with a bassline. A blend of nostalgic soul, funk, and spoken-word poetry, it hums before it speaks, swaying before it testifies. Since her debut album in 2000, Who Is Jill Scott? Words and Sounds Vol. 1, Scott has given Blackness—and her native North Philadelphia—the foundational centering it deserves: the fragrance of cocoa butter warming on brown skin, potato salad on white styrofoam plates, the humidity thick on summer evenings while the sun goes down. Her voice gathers these recollections. It calls in the cousins from the sidewalk, tells the uncles to mind the grill, lets the older women finish their stories without interruption. It is community scribbled in the pages of a notebook. But Scott’s Blackness is also kinetic: It sounds like double-dutch rhythms on pavement, rope slapping concrete in perfect time while sneakers tap the block. Her cadences pivot and play, bending phrases into jazz-informed stretches, turning seemingly mundane occurrences into bright melody.

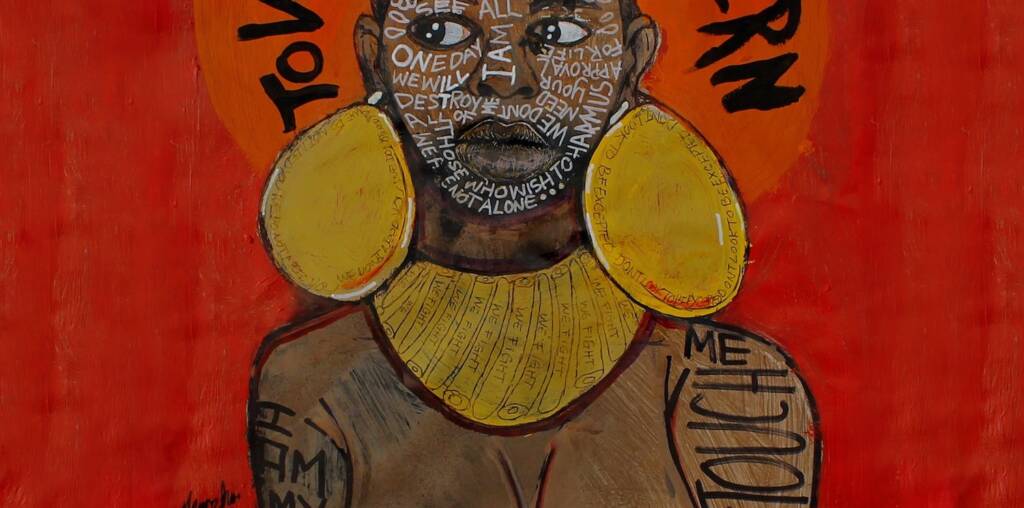

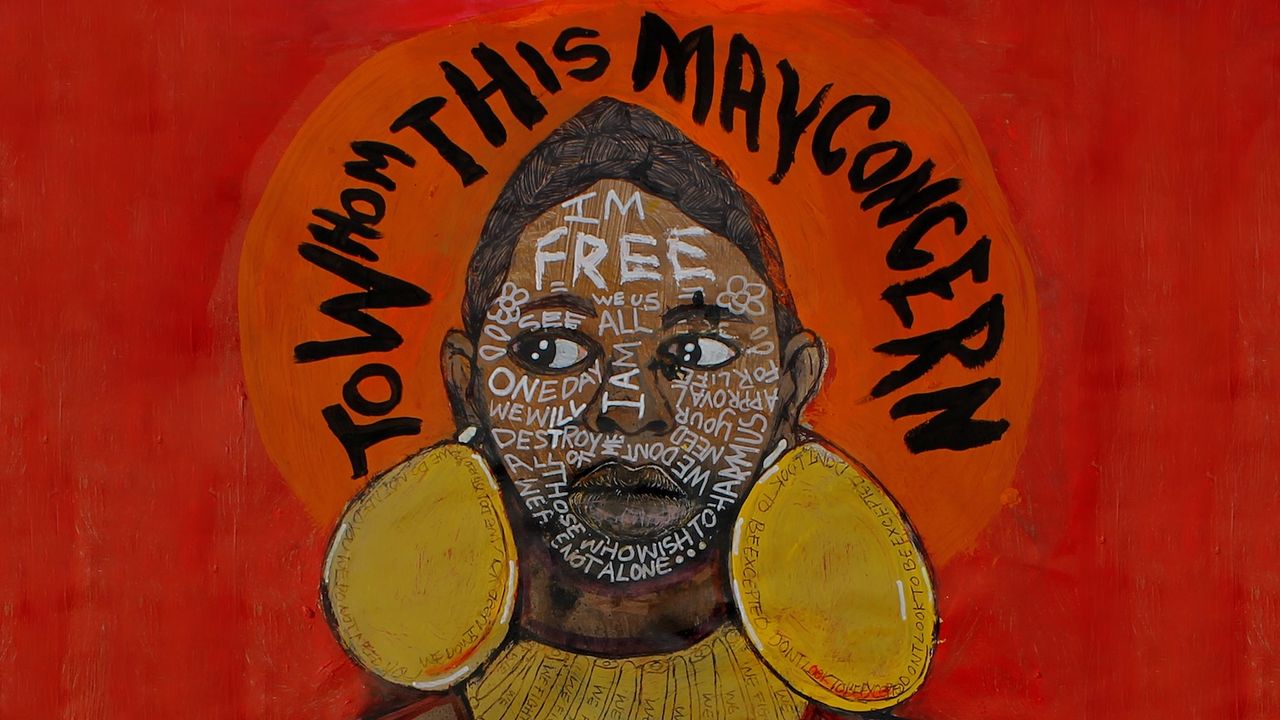

On her intrepid new album, To Whom This May Concern—her sixth studio LP and her first since 2015’s Woman—one can hear the lineage immediately: the syrupy stretch of ’70s groove, the blast of ’90s hip-hop, the swing of big band jazz, the meditative aura of the neo-soul era from which she emerged. Across several tracks, I can hear her honoring those who steadied her: ancestors near like her uncle Lonnie, as far as the poet Nikki Giovanni. The tonal choices across the album, with its lush basslines, head-nodding beats, and live percussion that feels like Sunday morning praise, suggest continuity with those who came before. To my ear, it coalesces Who Is Jill Scott? and 2004’s Beautifully Human: Words and Sounds Vol. 2 as music meant to evoke the past without treading all the way through it. Similar to how A Tribe Called Quest’s 2016 album We got it from Here… Thank You 4 Your service sounded like an updated version of the left-of-center hip-hop Tribe always made, Scott is experimenting while staying true to herself, not pandering to what’s hot.

No score yet, be the first to add.

There’s a throughline of redemption coursing through this LP, yet her comeback doesn’t sound tethered to public approval. Instead, this is a new, IDGAF version of Scott, who can still sing quiet-storm ballads but also talk shit about social media naysayers. “They stay chatting about my body on IG, say I’m a mean bitch, I’m in the illuminati,” she raps on “Norf Side,” one of several highlights. In years past, Scott could be best described as a purveyor of romantic love and sensuality. Not on this LP. “Pay U on Tuesday” is all swank and sass, a for us, not for them bluesy track about sidestepping energy-draining folks. The metaphor of deferred payment feels autobiographical—emotional debts, promises made and broken—yet the song’s brassy rhythm keeps it from sinking. It’s comedic, actually. Scott sings through a grin, refusing to let setbacks calcify.

In the weeks leading up to this album’s release, the press cycle framed the project as Scott’s triumphant return after a decade-long absence from the album format. The narrative was neat: beloved neo-soul luminary steps back into the spotlight, reminding everyone what they’ve been missing. Neat narratives rarely account for real life—especially not the kind of very public living that Scott has done. A decade is long enough for truth or myth to form. Long enough for divorce proceedings to become blog fodder, for interviews to be parsed into character studies, for the industry to shift beneath your feet. By the time Scott reemerged with singles and press appearances, the subtext suggested a confessional LP about her ups and downs away from the spotlight.

“I married a bitch,” she quips on “Me 4.” “I didn’t know, I went too fast when I shoulda went slow.” Another song like “Be Great,” with its ascendant horns and Second Line arrangement (thanks to the noted New Orleans bandleader Trombone Shorty), feels anchored in affirmation: After some time being down, Scott’s muscle memory kicks in and she remembers who she is, stepping back into a room she built. To that end, To Whom This May Concern might feel scattered to those wanting her more characteristic, sensuous R&B. But the album does a good job of flaring in different directions while keeping close to Scott’s artistic core. It occasionally sounds like a jukebox, and a song like “Ode to Nikki”—where she attempts to mimic Giovanni’s tone and cadence—doesn’t land. Yet the missteps are few, despite the crowdedness.

“Beautiful People” carries a gentle charge. There’s a glow to the arrangement, akin to 2004’s “Family Reunion,” that points out how Scott’s music functions as communal balm. Beneath the uplift is a woman who has seen affection curdle, as if love and loss somehow don’t pertain to the most visible. The song likens adoration to a whisper, a messy communion. “Yes, our love traversed the seas,” Scott declares. “Yes, our love is the art of war/Conquering all algorithms.” There’s that word: algorithm. The invisible curator, with its cold hand nudging taste, rewarding brevity, and flattening risk into whatever loops cleanly for 15 seconds. In the end, To Whom This May Concern moves as if untouched by it. Because who gives a damn when the results are this personal and resistant, when Black joy is this pronounced and unashamed.